Cloud Is Not for Everyone

My screaming intuition

Recently I have heard the message again:

There will be only public cloud, there is no other future for our planet.

It was not uttered by a sales representative of a hyperscaler, but by a CTO of a third party, a potential client. I have heard or read similar messages for several years now and every time my intuition kept (silently) shouting at me:

No, no, no!

But as is usual with intuition – it rarely surfaces details of what made her shout. Eventually, I found some time to yield to its pressure, worked on the topic, and now I publish the results.

In this post I evaluate the “cloud only” statement from the point of view of business-focused IT decision maker, that wants to know “is the cloud for us”.

As the topic of cloud adoption, or more broadly – decision making in modern IT – kept expanding in my mind I decided to divided it. This post is the first one, so bear with me and my shouting intuition. Maybe under your eye she will get shy and fall silent.

Impact of the "Cloud only" idea

I am not sure where the idea that only the public cloud remains came from. You cannot find it on any official pages anymore, but it lives like a meme in the sociosphere: it keeps replicating, mutating and comes back. And if taken at face value it has huge implications.

At the market level “cloud only” paradigm implies not only that adopting a cloud is inevitable for everyone, but also that there is no alternative – only the cloud remains. It sounds almost like a law of physics and who would fight the gravity?

Obviously, such a meme serves the cloud vendors, but what about individual companies?

At the individual company level, if you consider “cloud only” paradigm, you weigh a decision that is worth around 1%-2% of the yearly revenue, over many years [Footnote 1]. At this impact level, it demands some attention. Maybe this is what my underexpressive intuition was about?

Now, let me be more specific describing “cloud only” being adopted universally. It is a shift:

from

many thousands smaller, data processing facilities dedicated to and run by numerous companies

to the cloud

(few larger, shared data processing facilities) owned by couple of hyperscalers.

What would be the reason for something like this to happen, globally?

If we find an answer, we would know what were the driving forces, the arguments, and in the end – who would be benefitting from this – for whom is the cloud.

I was approaching the question from different angles. Let’s start with the look at the future of the clouds through the eyes of the historian ;).

Historia magistra vitae technologiae est 😉

Something similar must have happened in the past.

If we find case similar enough, then – assuming underlying processes (human behaviour; physical, economical, legal laws of the world) act per se the same – we may reason if the “cloud only” future is likely, and why.

What is the best possible lesson from the past?

We, as the civilization, went through technological revolutions already. There were several waves of changes at the turn of the 19th and 20th century: stationary steam engines, followed by mobile steam engines, then followed by electricity replacing steam. I focus on the newest one of these: electricity and mass electrification.

Let’s start with the today of electric power.

The electricity is ubiquitous. We all use it, but it is like water – we pay attention to it only, when there is outage. We do not think of where we get the electric power from, but it does not matter, as any appliance can take it from any power plant. Oh, and these power plants – these are huge facilities located far outside a layman’s sight. They provide electric power to every company and individual in the region, no company builds power plant for its own use.

Let’s see how the future of “cloud only” computing might look like.

The cloud computing is ubiquitous. We all use it, but it is like electricity – we pay attention to it only, when there is no connection. We do not think where our computations are done, but it does not matter because any application can run on any cloud. Oh, and these clouds – they do have huge data processing facilities located far outside a layman’s sight. They provide computing power to every company and individual in the region, no company builds data center for its own use.

The today of electricity is the future of cloud computing.

Is the yesterday of electricity, the today of cloud computing?

In other words: can we find enough similarities between the era where electricity was nascent to assume that future of the cloud will be similar?

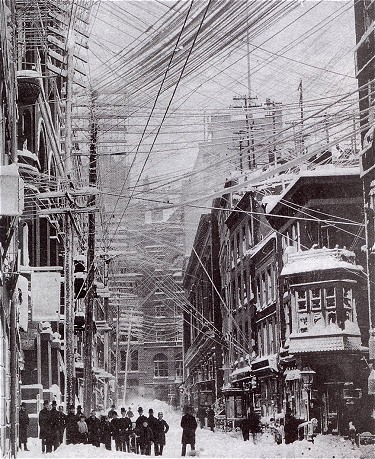

I did some research [Footnote 2]. The below paragraphs sum up, what I have found about the beginnings of the electricity. Let’s move now to ’80s and ’90s of 19th century, New York City. The picture from the times might help in our travel in time.

Electric power is relatively new, but it already seems to threaten replacing coal (and gas) as sources of heat, warm and power. Fossil fuels obviously had to be consumed on site, where the energy was needed. At that time, electric power plants are only a bit different from traditional ones. They are capable of powering the consumers (houses, factories) in ranges of kilometres, so still there are a lot of them needed, and by today’s standards their capacities are small.

There are plenty of variants of electric power generated (different voltages, different frequencies, direct or alternating) as different appliances have different demands. As a result, the sky over city is crisscrossed with web of lines – each dedicated to different current, from different plant to different client. Obviously, no easy switching between the providers and one cannot easily plug its appliance somewhere else and expect it to work.

There is a fierce competition within electricity market itself: the incumbent direct current against entering alternating current. This competition, later called Wars of the Currents, was not the fair and open duel of competing technologies on the ground of their pros and cons. It was actual business war for the nascent, but rapidly growing market, that was to change the way people lived. And this end seemed to justify the means: dishonest marketing, propaganda actions, lobbying, dirty money and rigging tenders and some other covert schemes, all to influence the administration and the public in one or the other direction [Footnote 3].

Maybe with the exception of the extremes and cruelties in the Wars of the Currents, the yesterday of electricity look alike to today of cloud computing.

The next paragraph describes the shift that happened in the electric power market.

In the end, after some further changes driven by technological, financial and legal forces, the industry went:

- from many small, local power generators powering each small house and factory,

- to consolidated, huge electric power plants [Footnote 4] of many orders of magnitude higher capacity.

- Number of players (companies) had been also going significantly down, through series of M&As. Number of offerings had also been significantly reduced down.

It is easy to continue building the analogy further. Instead, I ask this: have we just demonstrated that the same trajectory is very likely for the cloud computing?

Is the cloud really for everyone, just like electricity is?

My intuition fell silent.

What do you say?

Footnotes

Footnote 1

Rough calculation formula:

Total Annual IT Spend * Share of IT spend related to infrastructure

where:

- Total Annual IT Spend is 3% to 4% of revenue – for majority of industries, and across majority of years and geographies (See for example Gartner reports). It can be more for high tech sectors, or banking, but it is lower for heavy industry sectors.

- Share of IT Spend related to infrastructure covers hardware assets and related facilities and services, regardless of the ownership form (in other words: CapEx, OpEx and own labour cost of everything that is needed to provide IT infrastructure services. This share usually lands between 1/3 to 1/2 of the total IT spend.

The total impact may be higher if we consider impact of the change onto the data & application related parts of the operating model. The impact may be lower (I have seen situations, where it would be lower by 50%), if significant part of the hardware assets is not “cloud-movable” for architectural reasons (e.g. mainframe applications fall into this category).

Footnote 2

Footnote 3

Footnote 4

Sources (and great reading btw)

- Energy and Civilization: A History: Smil, Vaclav

- War of the currents – Wikipedia

- The Last Days of Night: A Novel – Kindle edition by Moore, Graham

- History of electric power transmission – Wikipedia

- How Edison, Tesla and Westinghouse Battled to Electrify America

- Industrial Revolution – Wikipedia

- Memetics – Wikipedia